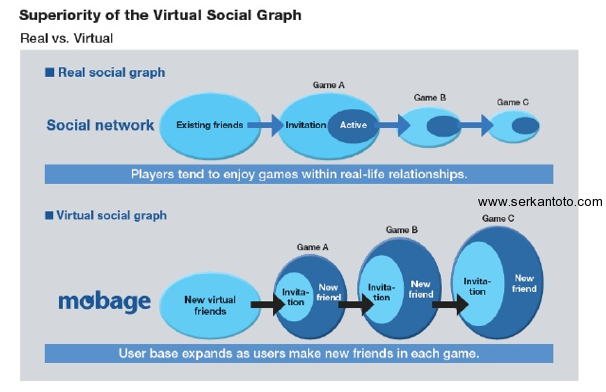

One of the key elements that gives Japan’s mobile social gaming platforms Mobage and GREE their “identity” is the concept of the virtual social graph. Simply put, the idea is to offer up a social environment in which the people the player interacts with are (mostly) strangers in real life.

Let me dive into this concept quickly before I get to the news that DeNA started connecting Mobage with Twitter.

As the main element of Mobage and GREE are games and not actions like exchanging messages, sharing pictures or posting one’s relationship status, your friends on these networks don’t have to be your real friends. That’s how DeNA and GREE explain the completely anonymous way their users interact with each other (absolutely nobody on Mobage or GREE uses real names or real profile pictures).

In fact, both companies don’t want players to reveal their real identities to each other: virtual-to-virtual interaction is fine, virtual-to-real “conversions” of relationships are forbidden, i.e. to protect younger players. Both GREE and DeNA employ hundreds of people who are actively screening messages in their platforms to ensure that these conversions – and other potentially harmful actions – don’t happen.

A completely virtual social network, the reasoning goes, is not only safer. It’s also the perfect structure to enable users to play which games they want, with whoever they want, and at which times they want – anonymously. Users can mass-invite others, send each other emails asking for support in games, or spend tons of money on games without anyone in the real world knowing about it (and without spamming real friends with requests and notifications).

DeNA contrasts the virtual social graph model against Facebook’s or Twitter’s real social graph model like this:

But I am under the impression that the company is starting to lose faith in this model, to increase engagement and the number of users.

Last month, Mobage in Japan and elsewhere started connecting with Facebook.

To be more concrete, Mobage users can now log in with their Facebook accounts, share game information on the Facebook walls of friends and invite their Facebook friends to play games on Mobage right from within those games. In addition, it’s now possible to register as a new user with an existing Facebook account.

So in other words, DeNA allows their users to mix their virtual social graph with the real social graph: the “pure” virtual social graph strategy which the company followed for the last five years (and which it used to explain Mobage’s success, as you can see above) is history.

And DeNA has just taken this to another level, as Mobage users can now invite their Twitter followers to play games with them. Those followers receive direct messages on their Twitter accounts that players can compose and send from within the games they play on Mobage.

These cross-platform friend invites are also possible via Facebook, and here is how this looks:

What’s interesting is that users are not obliged to reveal their Mobage IDs. As such, DeNA is providing the possibility to keep one’s identity anonymous (side note: with now over 30 million accounts, Twitter is a huge success in Japan).

The question is, however, how realistic this is: I, for one, would ask myself what the point is when somebody invites me to a game via a Twitter DM and wouldn’t tell me who they are on Mobage. I get enough invites for all sorts of games from many, many anonymous people on Mobage as it is, so that would make no sense.

And these cross-platform friend invites are not all: according to DeNA, it will soon be possible for users to post activities or achievements in Mobage games to one’s timeline on Twitter.

It’s not clear yet how exactly this will look (as with the friend invites, posting that information anonymously would only make limited sense), but it seems like the virtual social graph model is losing its appeal, at least for DeNA: rival GREE, at this point, isn’t connecting with any other social network.

N.B.:

I am not really sure what the legal implications of opening the virtual social graph are. For example, upholding an anonymous social environment was one way to make it difficult for older users to identify and connect with younger ones – which was in line with Japan’s strict youth protection laws.

But allowing Mobage users to connect with real-identity accounts on Facebook and Twitter opens the door for activities on external platforms on which DeNA has no say.